(published in The PIE News, April 3rd 2024)

Is the drive for internationalisation grinding to a global halt? Entry to major HE providers is getting tougher just as pressure rises within universities to attract ever greater numbers of international students.

Three major HE providers – the UK, Canada and Australia – are actively rebalancing international student entry policies. Domestically there are clear reasons for increasingly hazardous policy hurdles. From national sentiment towards migration to housing supply, governments face a serious balancing act.

The UK is reviewing the Graduate route visa and presenting student numbers as excessive migration. Canada has announced a temporary student number cap to tackle ‘sustainability’. Australia is stumped and considering what its education minister has coined ‘spiky ideas‘.

Yet a puzzle remains – why are major providers pushing dramatic policy shifts at the same time and what is driving the trend?

Old tensions come to a point

Patterns do not appear out of nowhere. The Trump presidency saw international students pulled into politics as the White House picked battles with specific countries over migration and security concerns.

More conservative circles in the UK also have long argued for student caps. Think tank Onward argued in a report in 2020 for international student caps, stating that universities had become too reliant on them.

At the crux of their argument was ‘resilience’ and ‘over-reliance’. The research argued that the reliance on overseas students was a point of financial fragility and represented over-dependence on China.

The report also raised concerns that international students were displacing local ones. As the international students pay high fees there is a strong incentive for the universities to prioritise them over local students, the report argued.

The critics may have been focused on security, but the over-reliance argument now sits at the top of priorities.

In the UK, the predominance of international student fees in university revenue streams, effectively subsidising sky-high operational costs, has become the key point of conflict between the higher education sector and policymakers. The universities need more international students, the policymakers want fewer.

Immigration politics, different stories

British politics has pulled students into already heated immigration debates.

At the end of 2023, UK home secretary James Cleverly announced a formal review of the Graduate Route, aiming to “prevent abuse” and “protect the integrity, and quality of the UK’s outstanding higher education sector”.

The decision was part of the government’s wider immigration plan. Net migration up to June 2023 was 672,000, lower than the level in December 2022, but still higher than the Home Office wanted.

This announcement was accompanied with a controversial hike in salary thresholds for migrant workers, shifting up to £38,700 from £26,200 – a figure high enough to effectively bar many international graduates from entry level graduate jobs.

Pressure on the Graduate Route could dramatically hit international enrolments. “The promise of post-study work was not a ‘nice to have’, it was a crucial factor in a family investment decision,” argued Ian Chrichton, CEO of Study Group, in a recent HEPI article.

“We urge the government to ensure it continues to support policies which are essential to the UK’s reputation as a welcoming study destination for talented young people from across the world,” James Pitman, managing director for the UK and Europe at Study Group tells PIE.

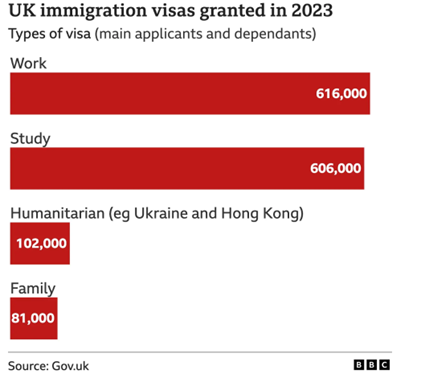

When you see study visas presented as a share of visa issuances, you get an idea of why capping students appears a quick political fix.

A BBC Report on the government’s failure to live up to its own immigration control pledges highlighted how significant a share of crude migration figures international students account for 606,000 of the recorded 1,405,000 visa issuances in 2023 and almost as many as work visas.

What the figures do not show is that students in general stay only for a few years and do not represent 600,000 new long-term residents in the UK. Some will stay longer to work, but only a fraction of the whole international student population.

Australia has a double challenge – public pressure to control international student intake and a dire need to fix a labour shortage.

Last year in April, Australia’s federal government started work to reform its immigration system, student immigration included. At the time, Home Affairs minister, Claire O’Neill, stated that the existing system was not set up to solve Australia’s most serious labour shortage since the Second World War.

According to Jason Clare, Australia’s Education minister, the rules are designed to ensure standards and fend off exploitation.

“The Migration Strategy changes enforce higher ethical standards and ensures high quality education and sustainable international education growth,” he has said.

“The Government has taken action to strengthen the integrity of the international education sector, and student welfare is our highest priority.”

Australia, like the UK, needed to tackle salary thresholds on visas, last year set at AUD 53,900. However, where the UK policymakers faced a backlash for unreasonably high thresholds, the low threshold in Australia means graduates qualify even when not landing the in-demand jobs related with their fields of study.

In Canada the problem seems to be too much success. Quickly following the UK’s tightening up of visa regulation, Canada joined the fray in January. The Canadian government announced a cap on study permits to 360,000, 35% lower fewer issuances than in 2023.

Total international students in the country reached 800,000 in 2022. Yet Canada has a different narrative to the UK, more in line with Australia.

“International students enrich our communities and are a critical part of Canada’s social, cultural and economic fabric”, opens a government press release from the Canadian Immigration office (IRCC).

The cap is officially to stabilise student numbers and is set to only be temporary. It will last two years, and existing permits are to be renewed as normal.

“We must tackle issues that have made some students vulnerable and have challenged the integrity of the International Student Program. This includes making sure we can manage the number of international students coming to Canada in a sustainable manner, while deterring any bad actors who pose a threat to the system,” the IRCC told PIE.

The Canadian sector remains optimistic that the new policies are temporary, and an effort recalibrate. Speaking to PIE at a webinar, Larissa Bezo, CEO of CBIE voiced that while the policy changes were not ideal, they do offer a chance to be strategic:

“If we look at this from 50,000 feet, what these policy measures do is afford us an opportunity to be more strategic and intentional to ensure a sustainable approach for the long term”, Bezo shared.

Housing pressure

Even if national narratives differ wildly over emerging international student policy turns, there is common ground on one issue – housing.

Housing supply is a national issue for Canada, the Canada Housing and Mortgage Corporation estimating in 2022 that 3.5 million affordable houses are needed by 2030 to restore affordability to the Canadian housing market. This was a driver for the newly introduced recruitment caps.

“[International students] are not responsible for the shortage of housing, but the growth in the arrival of international students adds significant demand for housing and other services that all Canadians must be able to access”, the IRCC told PIE.

Housing supply is also at the heart of student number debates in Australia. After reports in the national media that international student numbers were to be cut back, the government announced this was incorrect and no student caps would be introduced.

Not however before highlighting tension towards students. One opinion piece in a Sydney-based paper blamed rent prices on migration and called for tuition fee hikes for international students to tackle rent increases.

Students have feelings too

As important as the quality of education and its reputation to students is their perception of the country it is in. Demonise them too much and other locations look more attractive – a greater risk as more countries including China and India position themselves as education hubs.

Solutions to revenue issues such as a proposed international student fee levy in Australia, described as a ‘spiky idea’ by education minister Jason Clare, may assist financial woes but raise political pressure and long-term partnership sustainability.

The most recent Universities Accord interim report from the Australian Department of Education highlights the balancing act:

“Australia’s research excellence is well known, but it is built on uncertain financial foundations. These (…) cause us to miss opportunities to adapt, develop and localise knowledge to the benefit of industry, communities and the wider economy. Perverse financial incentives can cause institutions to make funding-driven rather than mission driven choices” states the report.

An underlying message is this: universities need money to operate, but they are more than their revenue. A university and its student body are part of a wider community. Both locality and students are part of the same community.

Introducing tougher entry rules is therefore a balancing act. Tip too far in any direction, and either revenue sinks, students feel disenchanted, or communities neglected. To use an HE buzzword, the see-saw of student visas is a truly ‘glocal’ puzzle.